1. Saying what goes without saying

Promises such as “increased productivity” and “lower costs” are tough to deal with because they are among the benefits of technology in general, and all B2B technology products I can think of promise them. On the other hand, if those are the main benefits, you cannot not mention them.

But if you’re aware that you’re dealing with what goes without saying, you’ll put more effort into graphics and animation. Showing specific costs being knocked down, or employees reassigned to more mission-critical work (e.g., from maintenance to develop and test) is more interesting and persuasive than mere talk about productivity and savings.

2. Telling people what they already know

Let’s say your target audience is compliance officers. The last thing they need to hear is that the consequences of ineffective compliance include loss of company reputation, customers taking business elsewhere, failed audits, heightened regulatory oversight, fines, penalties, and possibly people going to jail.

On the other hand, it certainly makes sense to make it clear at the outset that you understand that this is the difficult environment your prospect works in. So that you can quickly establish how your solution improves that environment.

A big part of the secret of how to limit a video to two minutes (or any short length) is not telling people what they already know — but rather sketching in that intersection between where what they know and what you know — and how that works to the prospect’s advantage.

So, here again, you can “sketch in” the difficult environment and bad consequences outlined above very quickly — in effect using your two minutes to say, “You recognize this problem, right? Well, here’s what we can do about it.”

3. Not telling people what they are seeing

If you’ve got software architecture to depict, or a business model, or a software product demo, the narration should work with the visuals to guide the viewer’s eye to what you want him or her to see. This shouldn’t require a lot of words — expressions like “throughout the entire lifecycle” or “drill down to the root cause” gets the idea across without a dreary recitation of each stage in the lifecyle or each step on the way to problem resolution.

I suppose these mistakes are all related to relying too much on tell and not enough on show. It can be a problem in the script development phase when the words don’t seem to be describing the problem or the solution very definitively. I always aim to have the narration come across as low-key and conversational. I understand that it’s natural for people reviewing the script to want to say more. Our job as producers is to make sure that, in the end, pictures deliver most of the message.

4. Not counting words

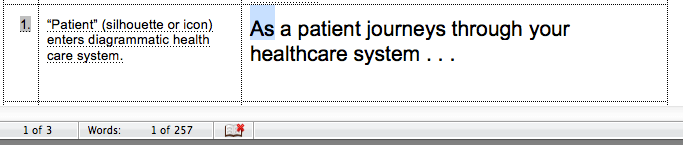

The first thing I do when starting to write a script is set up MS Word to show the text being spoken, and hide everything else (in our scripts, text describing on-screen graphics and animation). Words formatted as hidden text are not counted in the word count that appears in the message bar at the bottom of the screen.

-

Everything but the narration is formatted as hidden text. (indicated by dotted underlining). The selected word above is the first word that “counts” and the first word spoken. (A drawback of this method is that it’s easy to forget to un-hide the hidden text). About 260 words can be spoken (and listened to) pretty comfortably in two minutes.

If there are five benefits associated with some product feature, for example, the narrator doesn’t need to say much beyond “Check out these benefits,” as long as the benefits are clearly illustrated. The narrator can keep quiet and take a breath while the viewer engages with the graphics.

-

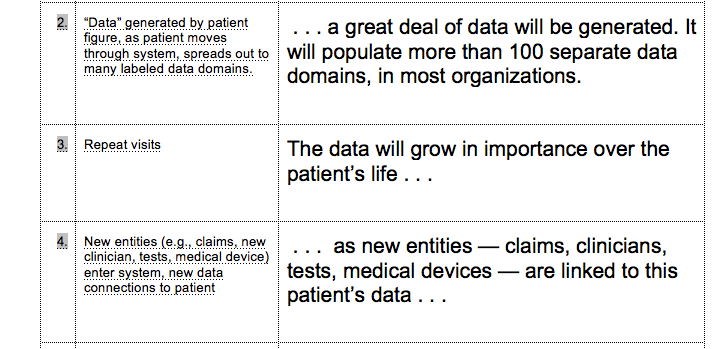

Coordinating visuals and narration. This is a first draft, so the description of visuals is left somewhat open. In scene 2, there will be “many” data domains shown. In scene 3, it’s not clear what “repeat visits” will look like, but, as they are not explicitly mentioned in the narration, they will need to be clearly labelled. In #4, if it turns out to be necessary to delete words, I would take out the “list” of data types. They will still appear on the screen.

5. Words that don’t count

When I’m trying to take out words, adjectives and adverbs are usually the first to go. For one thing, a system that is “secure” or a feature that is “innovative” it doesn’t become more secure or innovative just because we tack “very” or “highly” or even “patented” (although showing the patent award on-screen would be pretty persuasive).

For another thing, a good narrator can enunciate “it is secure” in a way that conveys unassailable security. A surprising number of words that could be essential on the page are superfluous in the ear —when the eye is kept busy.